New York, USA

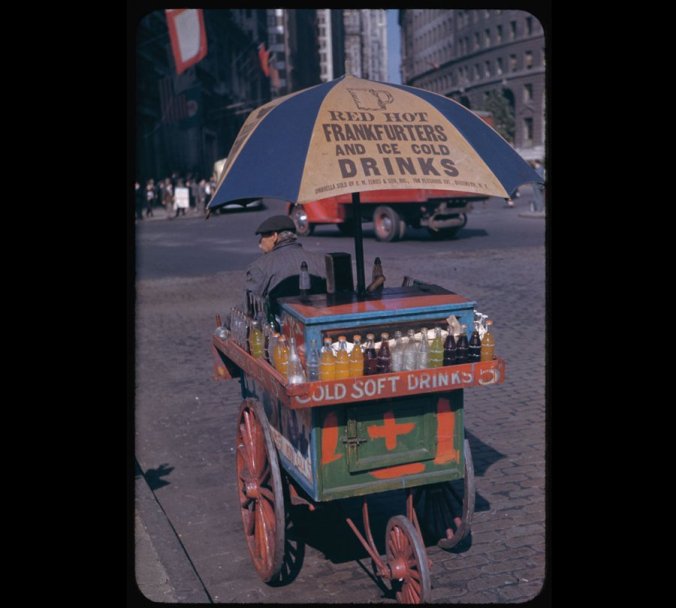

Un ambulante nella New York del 1941 dall’archivio fotografico di Charles W. Cushman

Joseph Cornell era un rabdomante di frammenti urbani. Entrava in antri da rigattiere, corteggiava le bancarelle; e scopriva tesori. Vecchi libri, dischi graffiati, copie di film in bianco e nero, stampe, cimeli teatrali, fotografie color seppia. E conchiglie e tappi e cigni di cristallo e compassi e bambole dalle labbra melanconiche. Gli toglieva la polvere, li faceva brillare. Creava un nuovo mondo per loro. Nello spazio di una scatola. Solo che le scatole di Cornell sono come gli spazi dei palcoscenici teatrali. Contengono storie e universi in sedicesimo. Ci si può viaggiare dentro. Cornell cominciò ad assemblare le sue prime shadow boxes negli anni ’30 del secolo scorso, quando percorreva a piedi Lower Manhattan, a New York, per il suo lavoro di venditore porta a porta. Come un poeta crea relazioni nuove tra le parole, l’artista eseguiva lo stesso processo con gli oggetti raccolti nei suoi vagabondaggi per la città.

Joseph Cornell visto dall’obiettivo di Lee Miller in chiave surrealista

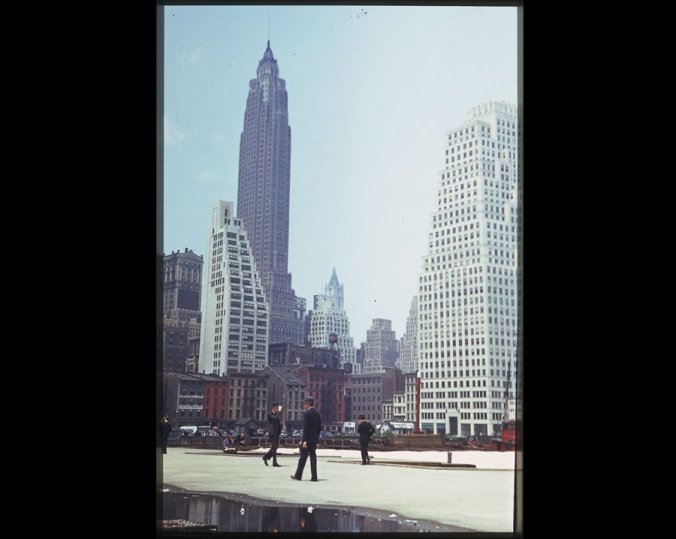

Ferries a Downtown, immagine di Charles W. Cushman

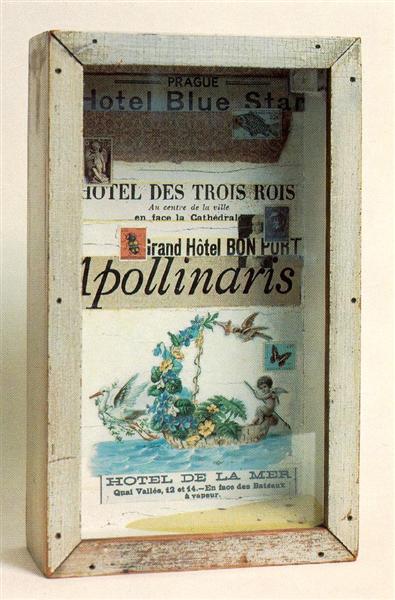

Un libro di Max Ernst, La femme 100 tetes gli aveva fatto intuire una via all’arte figurativa che non aveva bisogno di tela e pennello. Piuttosto dell’abilità e della pazienza di un cercatore, dell’intuizione di un indovino di analogie. Generalmente hanno un lato trasparente, in vetro, le scatole di Cornell. Sono vetrine di sogni. Alcune ricordano campionari di un commesso viaggiatore (onirico), o il laboratorio portatile di un chimico (alchimista), come la scatola che contiene i flaconi di vetro de L’Egypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode, cours elementaire d’histoire naturelle, con la “sfinge” che emerge dalla sabbia, i pigmenti come fossili naturali, la perla nella bottiglietta metereologica. Ad aprire i contenitori si rischia di liberare geni curiosi.

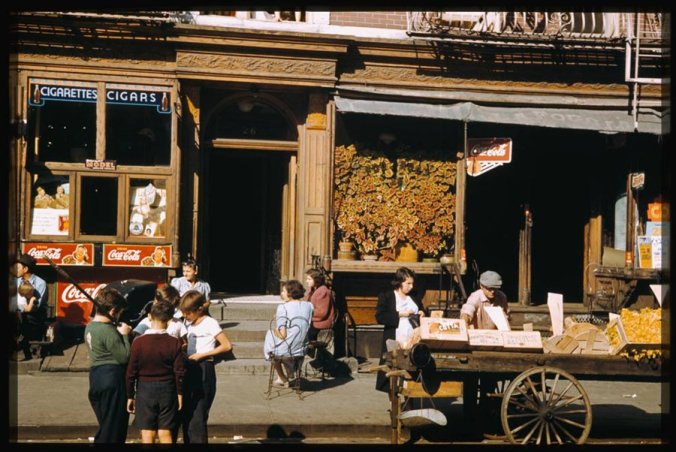

Una foto d’epoca del Garment District di Manhattan, una delle mete delle passeggiate di Cornell

La scatola intitolata all’ “Egypte deM.lle Cléo de Mérode ou course elementaire d’histoire naturelle”

I gtattacieli di Manhattan dall’East River (C.W. Cushman)

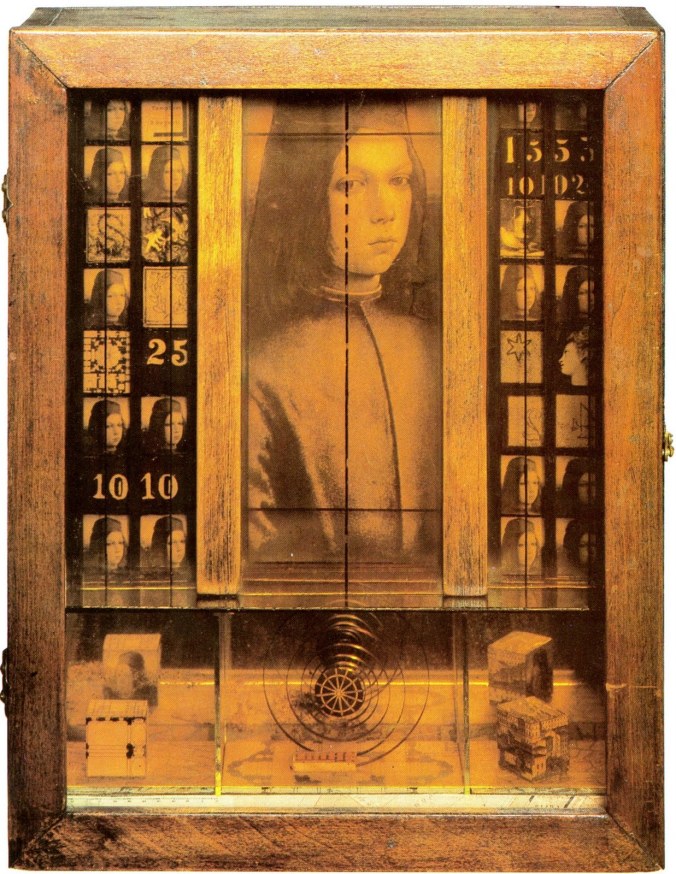

Un’altra, la famosa Medici boy, ha al centro una riproduzione del ritratto di giovane del Pinturicchio, un dipinto del Rinascimento inserito in un facsimile di slot machine americana dell’epoca. L’ipotetica leva potrebbe portare a Marcel Duchamp o, con un salto acrobatico, a Andy Warhol (entrambi conosciuti da Cornell). Joseph amava le combinazioni, i relitti che si perdono e si ritrovano, simili al soldatino di piombo di Andersen. Come lo scrittore di favole, amava le ballerine lucenti sul palcoscenico.

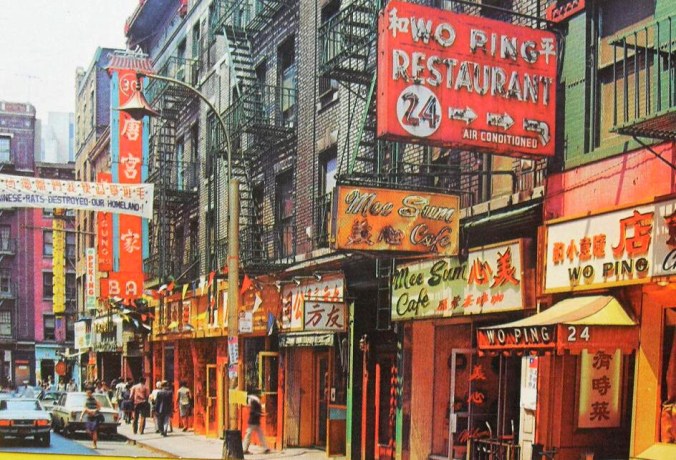

Charles Simic, il poeta serbo-americano, ha dedicato un libro a Cornell, Il Cacciatore di Immagini – che assomiglia a una delle sue scatole. Pubblicato negli Usa nel 1992 e tradotto in Italia da Adelphi nel 2005, è un pedinamento in lacerti e lampi per le strade di New York, dalla casa di Cornell in Utopia Parkway, a Queens, alle vie di Midtown e Downtown, allora poco di moda, tra negozi alimentari di immigrati e bazar di piccole cose. “Faccio un sogno. Joseph Cornell e io che ci incontriamo per strada. La cosa non è del tutto impossibile, avendo entrambi percorso a piedi le stesse strade” scrive. In realtà Simic passeggia tra Madison, la 42sima e Gramercy, tra il 1958 e il 1970, quando Cornell, per l’aggravarsi della malattia del fratello che progrediva con il crescere della sua fama nei circoli artistici, si era ritirato sempre di più nel suo scantinato di Utopia.

Una figurina sospesa di Joseph Cornell

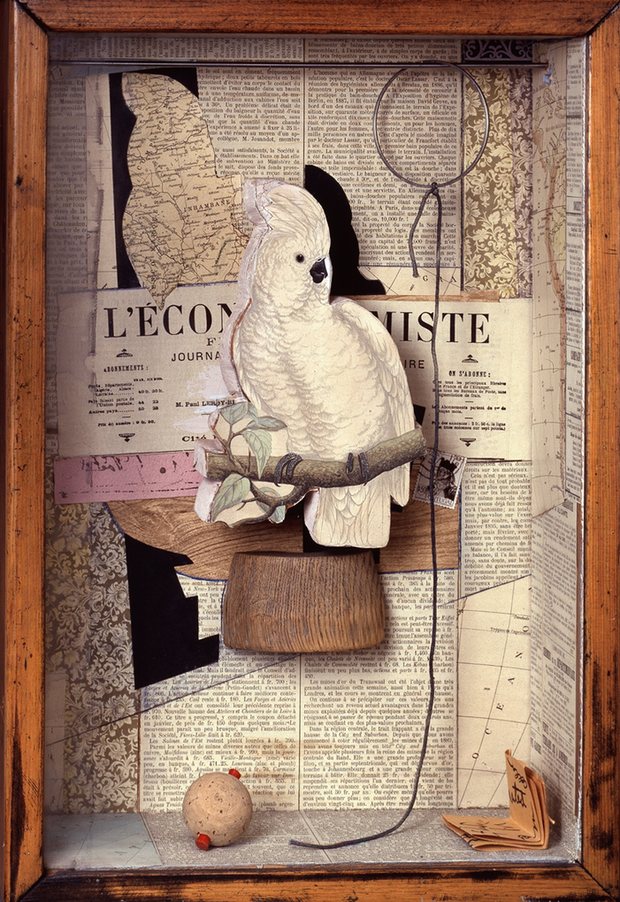

Incontro difficile, insomma, ma non impossibile. Simic usa lo stesso procedimento di Cornell: collega frammenti. Usa titoli evocative per i brani del piccolo libro: da Hotel Immaginari a Vecchia cartolina dalla Quarantaduesima Strada di Notte, oppure, Ciò che Mozart vedeva in Mulberry Street. Prova a tradurre in letteratura l’atmosfera sospesa dei contenitori usciti dall’utopico scantinato: ogni scatola, un brano. Ci sono citazioni dai taccuini di Cornell, nel libro. Immagini di un cacatua, vicino all’East River, bolle di sapone, e alberghi “fuori luogo”. Simic scrive da innamorato. Condividono, ne è certo lo scrittore, la stessa musa. Quella che presiede a una memoria dispersa, dove l’epifania è in una bambola sospesa da fili di burattino in una scatola.

La casa di Cornell a Utopia Parkway, nel Queens

La Medici box con il ragazzo del Pinturicchio

Cornell, nato a Nyack, un villaggio sull’Hudson, non viaggiò mai fuori dallo stato di New York. E dopo essersi trasferito nella sua casa nel quartiere di Queens, raramente usciva dalla città. Eppure era un viaggiatore instancabile. Anche se i suoi viaggi partivano dalle strade di Manhattan per inoltrarsi in luoghi dell’immaginazione. Curiosissimo. Timido fino alla patologia, ma non pauroso. Non riuscì ad amare l’adorata Lauren Bacall (che viveva a Uptown), che compare in una scatola, né le ballerine lucenti che pure frequentò. Conobbe molti degli artisti surrealisti europei che lo avevano ispirato, anche se si sentiva un loro cugino lontano. “Non voglio fare magia nera” diceva. “Solo magia bianca”. Fu intimidito da Dalì che lo accusò di aver copiato una tecnica di collage di inquadrature per film surrealisti nel suo Rose Hobart. Il mondo dell’arte lo scoprì nel 1932, la sua fama crebbe negli anni, pur restando una figura appartata. In una sua mostra, mise le scatole-vetrine all’altezza di un bambino. Bisognava ritrovare un’ingenuità ardente per viaggiare con Cornell. Oggi, se vi fermate a guardare i nuovi condomini scintillanti di cristallo e acciaio tra Madison e Chelsea, tra Tribeca e Seaport, provate a immaginare una scena allestita da Cornell, dietro le vetrate di un appartamento milionario. Forse vedrete una modella invece di una ballerina, ma dietro di lei potreste scorgere un cacatua che si liscia le piume sul tramonto.

Lower East Side, 1941, C. W. Cushman

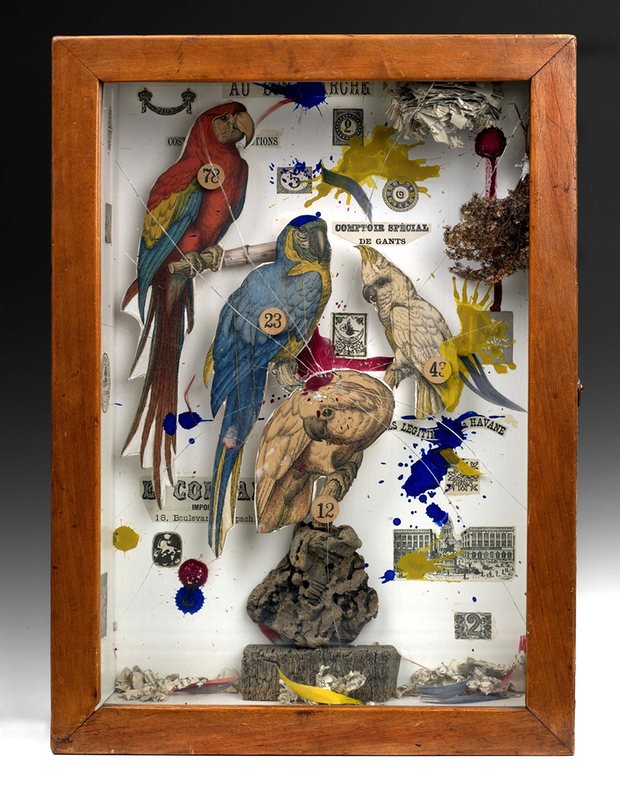

Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery di J. Cornell

Il nuovo grattacielo residenziale One Madison Park

Suonatore di fisarmonica nella subway di New York in una vecchia foto di Walker Evans

TWO MEN , TRAVELLING INSIDE A BOX

Lower Manhattan shot from Jersey city by amateur photographer Charles W. Cushman in 1941

Joseph Cornell was a urban diviner of scattered fragments. He found his way through the cavernous entrances of bric a brac shops; he slowly pursued the stands in the flea markets and along the streets of Midtown Manhattan. He discovered little treasures. Like three original drawings for Antoine de Saint Exupery’s first edition of The Little Prince. In his eyes, though, the beauty was in the broken relationships of the objects. A connection he tried to re-create. He bought old books, scratched vinyls, sepia photographs, shells, prints, crystal swans, corks, compasses, rubben balls, ballet relics, dolls with melancholic lips. He took the dust off. He staged combinations of them in boxes. Scenes of souls, lost & found. In the boxes the objects shine again. New connections mean new stories. Cornell’s boxes are miniature worlds you can travel through. Not by chance a retrospective exhibition dedicated to Cornell’s work at the Royal Academy in London in 2015 was titled Wanderlust.

Old Chinatown, NYC

Un ritratto di Joseph Cornell

Cornell began to assemble his shadow boxes in the 30s of last century, when he toured the streets and the avenues of Lower and Midtown Manhattan as a door to door seller. Like a poet with words, he created new unusual relationships among the objects collected along his wandernings.

Collecting salvage on Lower East Side, 1942 (C. W. Cushman)

La Femme 100 tetes, a book by surrealist painter Max Ernst gave him a hint of ways to make visual art with no need of brushes and canvases. The art of re-inventing things through combinations, a way similar to the one of an alchemist and a searcher. Most of the Cornell’s boxes have a glass pan you can peep through, to catch suspended actions in magical scenarios. Others recall samples travel cases or weird chemical field test kits like the small glass bottles in the box L’Egypte de M.lle Cléo de Mérode ou cours elementaire d’histoire naturelle, where the image of this famous dancer become a sphynx rocked by sands, a lost pearl calls for some weather forecast and dense pigments conjure the natural history of fossils. The Medicis boy box, instead, looks like an incongruous slot machine, centered on a cutted replica of Pinturicchio’s Portrait of Young Man, a Renaissance masterpiece. You can guess that if you pull to play, Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol could as well jump out as surprise jollies (they both were Cornell’s acquaintances). Joseph tried sample “microverses” with shop relics, he crafted new destinies for abandoned things, as it happens to the tin soldier in Andersen’s tale. The two, after all, shared also a romantic unconsummated lust for pretty female dancers.

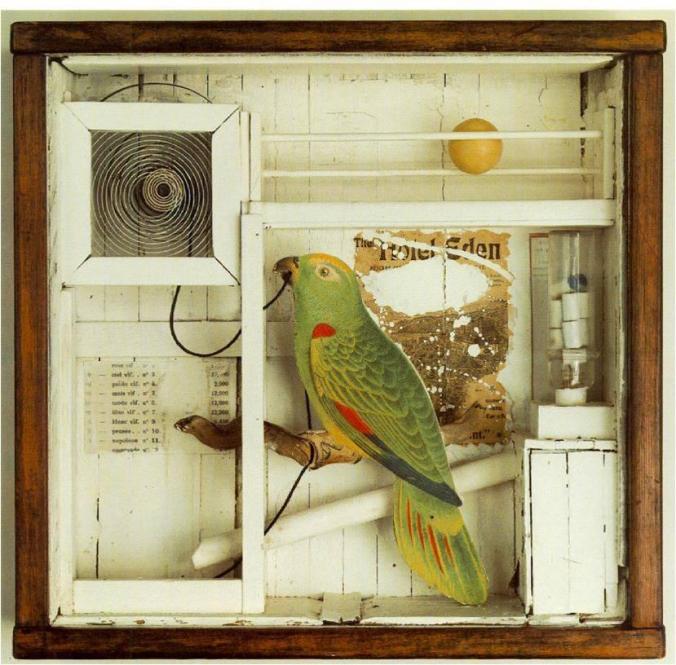

A Parrot for Juan Gris

The American-Serbian poet Charles Simic wrote a peculiar book on Cornell’s works and wanderings – that is organized in the same way of many of the artist’s boxes. Dime-Store Alchemy is the apt title of the book (New York Review Books Classics): Simic juxtaposes words, chapters, images as Cornell did in his boxes with found objects. To create a sense of mistery, some subtle special effect, an evocation. Published in 1992 the book is also a personal shadowing of Simic on Cornell, from street to page. Simic indeed tried to remake the boxes in his short poetic proses. In the preface he tells about a dream he had, about meeting Cornell in Midtown Manhattan. Difficult but not impossible, because they were both walking down the same streets between Empire State Building and Turtle Bay from 1958 to 1970. But in these last years, Cornell’s walks were sparse. He used to be more reclusive, to assist his ill brother and working in the basement of his home in Utopia Parkway. To translate the atmospheric boxes in prose, Simic connects fragments.

Charles Simic

On the page, we meet the same nostalgia for an unknown place as in the imaginary hotels on the French Riviera, the easy trick of suspended dolls, the partial worlds in the postcards, we spy on what Mozart watched on Mulberry street. A cacatoa plumage lights up grey buildings along rarefied afternoons, and the reader-viewer finds himself enchanted on a mask of a dead poet. Cornell was born in Nyack, a small village on the Hudson – he never ventured outside the state of New York. After setting in his house in Queens, he rarely went out of the city. Nevertheless, he was a tireless, curious traveller.

Lauren Bacall box

Bacall Smoking

Cornell was shy at a pathologic level, but not timorous. He did not succeed in reaching the beloved Lauren Bacall (who lived uptown). He put her in a box though. On the other hand, had few ballerinas among his acquaintances, but contacts were far from physical. The closest thing to a relationship was with the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, still a platonic one, as it seems. Cornell, after the war, met many of the surrealist artists who inspired him in New York. He considered them far relatives, at the end. “I don’t make black magic” he repeated. “Only white”. Probably he was shocked by a boisterous Salvador Dalì at the screening of his montage -film Rose Hobart: the Catalan artist was indignant to see that Cornell applied to his movie a similar images-collage technique Dalì himself deviced for his surrealist movies. Lesa Maestà! Even if I can well image Dalì mustaches in a Cornell box…

Rose Hobart film photogram

Salvador Dalì

The art world discovered Cornell in 1932 and he exhibited his dreamy objects in several occasions. His fame grew along the years. In a late show he set his boxes at the height of a child. You must find again an ardent naiveté to enter his worlds. To travel with him. Today, if you walk down the Cornell’s streets and stop to look at the new brand shining condo towers of steel, concrete and glass in Midtown and Downtown, from Sutton to Soho, from Chelsea to Seaport, try to look through the glass walls: maybe you will see a model at the photo shoot, instead of a ballerina, but you could sight, in the reflections, a cacatoa preening his feathers in the sunset.

Brooklyn Bridge in 1941

Walker Evans, girl in the Subway

Brand New Manhattan skyline: 50 United Nation Plaza Condo along with the Chrysler building

Chelsea Reflections, NY

Cornell’s Hotel Eden Box

Vintage New York from the camera of Margaret Bourke-White